My name is Vanna Walsh. I’m a free-lance-writer (published many times). I spent a month in China travelling with Wendy Wu’s China Highlights tour. And was impressed by what I saw and the way the tour was organised. I was inspired by many sights on this tour and, as soon as I got back home I wrote this piece. Wanting to communicate the elation I was feeling while climbing the Great Wall of China. At the moment I’m transferring my tour diary and notes on the computer in view of writing a travel book on the experience.

THE DAY I BECAME A HEROINE OF CHINA by Vanna Walsh

We were not prepared for the Great Wall. From Beijing we had been on the coach for an hour and a half, travelling in a bubble of smog. Unexpectedly we made out mountains on the horizon and, as we approached, the smog lifted. We glimpsed, in the surprise of the clear air, the grey, long, sneaking Great Wall. A great, sinuous, ancient dragon resting fully stretched on the mountain. As the coach neared the pass and the view opened up we saw the old serpent did not only stretch at great length up to the mountain in front of us but slithered powerfully along the ridges and crests of the nearby mountains so far until it was lost in the horizon.

The old beast is more than 5.000 km. long

The old beast is more than 5.000 km. long

It stretches from the Shanhaiguan Pass, on the East coast, to the Gobi Desert in the West. It is estimated “to have been constructed by one million people. Many of whom lost their lives building what was believed to be an impenetrable line of defence.” Most Chinese people still have a communist set of mind. When our guide, the son of parents who had fought with Mao’s army and participated in The Long March, declaimed these words, we could hear the pride of the common people for a job well done, for suffering and dying for the cause of defending their own country. Our guide’s voice rings with satisfaction. The Great Wall, he says, is built not only of mud and stones but also with the bodies of countless workers.

Our guide knows Australian’s take on the Great Wall!

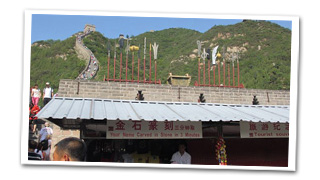

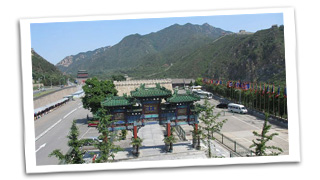

He jokes that great as it is, it hasn’t kept the ‘Rabbit Mongol’ out of China. We tumble out of the coach not knowing where to focus. There is The Wall on two sides, on two mountains linked by the pass; we see temples on the JuYong Pass where we are parked; colourful banners fluctuating in the breeze; and, as always, crowds of people. We’re shepherded through a revolving gate and informed we’re free for four hours to do as we please. I’m standing in the middle of it all, absorbing as much as I can. The Wall looms in front of me, vertically gripping the side of the mountain, jutting boldly up to the summit and then continuing its grip on the other side of the crest until it reaches the other mountain’s top, continues again on its sides and then disappears in the very far distance.

There are twelve ‘Beacons’ on this Pass.

Twelve forts manned by soldiers who, from its walls, looked out for ‘rabbits’: for the Mongol enemy. The immensity of it all is distracting me. I don’t know where to look. At last, I begin to walk up the steps. Along the steps, on the wall, there is a climbing-chain to help the walkers. I ignore it. The first few steps are of a normal height, easily manageable, but suddenly they become as high or above my knee: the walk up the Wall becomes a climb up the Wall. Step by step I climb up, stretching my legs at full height and length. I’m surrounded by climbers who go up at different speeds, stop and start, wipe the sweat off their faces (it is 32 degrees and only the beginning of Spring), look around and take a breather.

I reach first ‘Beacon’ and take time to look at the shops, at the side of the fort, selling Wall-merchandise. The day is now clear and the visibility good. In the valley below, on the right, there is a small village. I follow with my eyes the Wall on both sides of the Pass asking myself how did those men cut into the hard rock of the mountains, how they climbed up such steep crests carrying tools, materials and provisions. Many people are coming down: red-faced, sweaty, breathing heavily but smiling and stopping frequently to take photos.

I reach first ‘Beacon’ and take time to look at the shops, at the side of the fort, selling Wall-merchandise. The day is now clear and the visibility good. In the valley below, on the right, there is a small village. I follow with my eyes the Wall on both sides of the Pass asking myself how did those men cut into the hard rock of the mountains, how they climbed up such steep crests carrying tools, materials and provisions. Many people are coming down: red-faced, sweaty, breathing heavily but smiling and stopping frequently to take photos.

The further up I go the more the steps change.

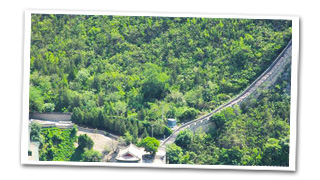

The majority are as high as my knees, some higher, a few shorter; some are broken or split or uneven or consumed by time and weather. It is not an easy climb. I approach the second ‘Beacon’. It has a shop and a display of ancient weapons on its courtyard. I stop here to admire them.By beacon number six, shops are replaced by stalls. My steps are harder to negotiate. I keep going up by fully stretching my legs and levering myself up by using the lower-back muscles. At Beacon number ten there are no stalls selling souvenirs and the crowd of walkers has thinned. There is nothing at Eleventh Beacon, only silence and a few people concentrating on the task of climbing. I’m beginning to tire. Slowly, methodically, I keep going.

At last, I reach Twelfth Beacon, the top of the Pass.

I’m short of breath, very hot and sweaty.  There are only the mountains, the Wall snaking up on them and not many people. I go inside the fort, ascend the steps up to the roof. I look at what the ancient soldiers were looking at and for. The mountains, the Wall, thick vegetation, the sky rolling over it all and constantly changing. It must have been a lonely tour of duty. Very hot in summer and very cold in winter, it must have required concentration and sharp eyesight to scan the surroundings for the enemy. Descending is easier than climbing up. At the Tenth Beacon, I buy a plaque where my name, day, month and year of my climb are carved. At the car park, I have barely time to step on the coach before it starts its way back to Beijing. When our guide hears of my exploit he declares me “A heroine of China”. He explains that, after The Great March, whose most difficult section was The Great Wall, Chairman Mao wrote “a very beautiful poem”. Which praised the people who had taken part in it as “Heroes and Heroines of China”, proclaiming that only the people who had participated could call themselves “True Chinese”.

There are only the mountains, the Wall snaking up on them and not many people. I go inside the fort, ascend the steps up to the roof. I look at what the ancient soldiers were looking at and for. The mountains, the Wall, thick vegetation, the sky rolling over it all and constantly changing. It must have been a lonely tour of duty. Very hot in summer and very cold in winter, it must have required concentration and sharp eyesight to scan the surroundings for the enemy. Descending is easier than climbing up. At the Tenth Beacon, I buy a plaque where my name, day, month and year of my climb are carved. At the car park, I have barely time to step on the coach before it starts its way back to Beijing. When our guide hears of my exploit he declares me “A heroine of China”. He explains that, after The Great March, whose most difficult section was The Great Wall, Chairman Mao wrote “a very beautiful poem”. Which praised the people who had taken part in it as “Heroes and Heroines of China”, proclaiming that only the people who had participated could call themselves “True Chinese”.

So, here I am – a Heroine of China and a True Chinese.